Interested in Treatment?

Get Treatment articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Treatment + Get AlertsEvery wastewater professional in western Massachusetts knew the U.S. EPA and state regulators were looking at the Montague Clean Water Facility.

When the plant supervisor position opened up September 2019, no one touched the hot potato except Chelsey Little. “The only way I saw was up, and the challenge was exciting,” says Little. Hired in March 2020, she had only four years of experience.

She walked into a perfect storm. In 2015, and as part of a five-year trial, the 1.83 mgd (design) activated sludge plant was reconfigured to high-rate anaerobic digestion. In 2017, two major paper mills ceased operations.

Without the pulp and paper waste, sludge consistency changed almost overnight to a soupy mix. Over time, TSS short-circuited into the effluent and triggered permit violations. Flying under the radar, a food production facility contributed to TSS and dumped acidic cleaners and lactic acid into the sewers. An aquafarm added more TSS. Process control became erratic and frustrating.

Over the next two years, Little and her multitalented team restored compliance, showered the plant with much-needed love and engaged in community outreach. In 2023, the New England Water Environment Association honored Little, 35, with the William D. Hatfield Award.

Background

Little never fit the typical mold. While classmates watched cartoons and read comic books, she watched the Discovery Channel and read National Geographic. “I loved biology, but didn’t pursue it until after I married and had two children,” she says.

In 2016, Little earned a bachelor’s degree in biological sciences from Southern Vermont College, graduating summa cum laude. Then came a master’s degree in environmental public health from the University of Vermont while working as the laboratory manager at the Greenfield (Massachusetts) Water Pollution Control Plant.

“My husband, Todd, is a water and wastewater operator and we talk shop,” says Little. “He mentioned that the many small drinking water systems in our area had no nearby state-certified drinking water labs. With our backgrounds, we opened Pioneer Valley Environmental Laboratories in June 2016.”

By April 2018, the highly successful part-time enterprise forced the couple to decide between running it full-time or remaining in their present occupations. They chose the latter for the security it gave their three small children, and because Little realized how much she loved and missed treating wastewater.

After a brief stint as chief operator at the 1 mgd (design) Northfield Water Pollution Control Facility, Little took her current supervisor position.

Dream team

When Little wasn’t writing effluent and industrial pretreatment reports or high-flow management plans for the regulatory agencies, she was the plant’s self-proclaimed project manager.

“I told my guys what to do and they did it,” she says. “By keeping the work in-house, we saved the town hundreds of thousands of dollars.”

Her team includes Tim Little, foreman, operations manager and brother-in-law; operators Tim Puera, Adam Kleeberg and Samuel Stevens; Noah Diamond, laboratory manager, and Patricia Holloway, administrative assistant. Puera is also a mechanic, Kleeberg a licensed plumber and Stevens a carpenter.

Their most ambitious undertaking was installing the ES-302 two-channel Volute dewatering press (PWTech [Process Wastewater Technologies]). Over two months, they poured the concrete pad and trenched in the drainage. Kleeberg oversaw plumbing the return activated sludge feed and flowmeter, while Stevens supervised running the conduit and pulling the wires.

“Specifications came with the press and PWTech provided a checklist of what to do, and the plant staff put it together,” says Little. “Once complete, a PWTech representative came to inspect and activate the press. It began running in early January 2022.”

Today, the press turns sludge at 1.5% solids into cake at 26% solids for composting. The plant has been compliant since January 2022. Little estimates the in-house installation saved the town more than $100,000.

With the acquisition of a 21,000-gallon storage tank in February 2023, the facility gained the capacity (50,000 gallons total) to again become the regional biosolids dewatering hub. Until then, surrounding communities paid haulers to transport it long distances for dewatering.

“We initially accepted three 9,000-gallon loads per week, but we anticipate handling eight such loads per week,” says Little. To further increase revenue, she ordered a feasibility study based on opening a regional composting facility.

Sleeping tigers

While some operators dread regulators, Little views them as assets. She has worked with Dan Kurpaska, a state Department of Environmental Protection wastewater management regulator, and Jack Melcher, a U.S. EPA enforcement officer, for six years.

“They are a wealth of information and anxious to help solve problems,” says Little. “The key is to keep them apprised of what is happening.”

Cases in point were bulking/settling occurrences at the plant and fluctuating biology and chemistry with no obvious cause. Little reported the process control situation to Melcher, who uncovered industrial users in significant noncompliance with pretreatment requirements.

Little’s investigation discovered that fermentation at the soy-based food facility produced exopolysaccharides, which caused settling problems at the plant and had to be wasted. “In addition, their wastewater had pH levels of 1 or 2, and 5 is the legal limit,” she says. “Once this and other rogue facilities became compliant, we regained process control.”

Until recently, industrial clients were sampled annually. “Part of our problem was lacking the personnel to run a comprehensive industrial sampling program,” she says. She sought funding, then hired Diamond and tasked him with sampling the companies quarterly.

The case convinced Jay Pimpare, EPA pretreatment coordinator, to invite Chelsey to present “How Pretreatment Changes Impact Process Control” at the New England Regional Pretreatment Coordinators Conference and the New England WEA Spring Conference on Innovation and Resiliency.

Her conclusion advised operators to pay attention to their industrial clients and to unusual process conditions: “Take time to investigate, and above all sample, and sample often.”

Plant improvements

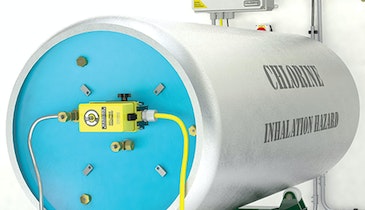

The consent orders included upgrades, and the removal of two 1-ton chlorine gas cylinders in the dosing room was first on the list. Plans from an engineering firm split the room into two, each with a 500-gallon liquid sodium hypochlorite tank.

Over winter, the team worked after hours for six months to complete the remodel in time for the chlorination season beginning in April. Little estimates that not hiring a contractor saved more than $200,000.

The plant’s multiple sumps required quarterly cleaning by an industrial company. “Service calls cost $2,000 to $4,000,” says Little. “We wanted to buy a small vacuum tank, but needed a trailer for it.”

After some networking, the public works department in a neighboring town offered a decommissioned two-wheel LED display trailer. The team added two front wheels and welded lots of metal to anchor a 450-gallon vacuum tank with a 5.5 hp gasoline engine (Brenner-Fiedler).

Other improvements included updates to the indoor and outdoor lighting, pouring a concrete pad for the solids frac tank ramp at the head of the operations building, and the purchase of a milling machine.

“Ordering parts for the four-channel Fournier rotary press cost $5,000 per component,” says Little. “Now Tim Puera mills them.” The press dewaters primary sludge.

While researching environmentally friendly polymers to replace the synthetic product in use, Tim Little found Tidal Clear (Tidal Vision Products), a water-soluble chitosan synthesized from the shells of harvested mud crabs.

“Chitosan is a close derivative of chitin, the second most abundant biopolymer in the world,” says Little. “Our initial jar tests showed chitosan compared with the synthetic flocculant in performance and price, but we want to run more trials with the company.”

Public outreach

As Little dealt with the plant’s physical needs, she stayed focused on her goal to change the public’s perception of it: “I wanted people to know that our role in the community is to protect their health and ecosystems, but we didn’t make a good first impression. All drivers saw from the road was the building’s ugly gray brick wall.”

Working with a committee, Little invited local artists to design a mural highlighting water ecology, the Connecticut River Watershed wildlife, and the interconnected ecosystem.

After reviewing 23 submissions, the committee selected Lahri Bond to paint the mural on a 10-foot-diameter aluminum disk. It was secured to the wall and unveiled during Earth Day in April 2022.

The town’s $2,500 investment produced better than expected results. “The mural has become our logo and is highly visible from the road,” says Little. “People love it and want us to sell T-shirts with the image on them.”

With the mural in place, the team noticed the dead grass and bare ground in front of the building. “I thought planting a pollinator garden to attract butterflies and bees would be beautiful and illustrate again that treating wastewater is about the environment,” says Little. Last spring the team planted flowers, trees and bushes irrigated with plant effluent and fertilized with composted biosolids.

Little reports that the facility has remained compliant. She still attends town hall meetings and community events to remind the public that “the treatment plant is at the river and operated by certified professionals.”