The eCrusor (Veolia Water Technologies) de-packages food in plastic jars without shattering the brittle plastic lids.

Interested in Dewatering/Biosolids?

Get Dewatering/Biosolids articles, news and videos right in your inbox! Sign up now.

Dewatering/Biosolids + Get AlertsThe Hermitage Municipal Authority started adding food waste to its biosolids in 2014 to produce more methane for its combined heat and power system.

At first the wastewater treatment plant handled only liquid waste from a pair of food producers but over nearly 10 years the menu options increased substantially. Canned soft drinks? Hermitage can handle that. Fruits and vegetables in plastic or cardboard crates? They’ll take it. Mayonnaise in plastic jars? Send it over.

The authority found multiple sources of organic material to add to the anaerobic digesters while creating a market for processing food waste in an environmentally responsible way. “We didn’t actually have to look for material — it started finding us,” says Thomas Darby, manager of the authority and superintendent of the Hermitage (Pennsylvania) Water Pollution Control Department.

Three digesters

The Hermitage treatment plant (7.7 mgd design, 3.5 mgd average) has a headworks with fine screening (Jones & Attwood) and three sequencing batch reactors with aerators (Evoqua Water Technologies). The effluent is UV disinfected (Trojan Technologies) and discharged to the Shenango River.

Biosolids go to gravity belt thickeners (Evoqua) and then to feed sequencing tanks for mixing with food waste. From there the mixture goes to a thermophilic digester (140-145 degrees F) for 48 hours, and then to two mesophilic digesters (98 degrees F) for 21 days.

The digesters have cannon mixers (Veolia Water Technologies) that use bubbles of the biogas to constantly mix the contents. The resulting biosolids qualify as a Class A product that is trucked to a farm. The biogas is captured in a 100,000-cubic-foot storage ball, scrubbed to remove siloxanes and hydrogen sulfide, and then chilled.

The scrubbed biogas feeds a 600 kW Caterpillar engine-generator and a 375 kW Nissen Energy unit. The two produce nearly all the plant’s electric power plus process heat for the treatment plant. “If everything is running and we’re at full operation, which means all the processes are working properly and the digesters are all online, we can zero out our electric bill,” Darby says.

Liquids first

The first source of food waste was a food distributor that had been landfilling expired milk, cottage cheese and other products in one-gallon plastic jugs returned from stores. The wastewater department used a perforator (R.E.M.) that punched holes in the jugs to drain the liquid. That worked fine.

The next source was a maker of ice cream cones that sent truckloads of liquid, pumped directly into the hydrolysis tank used to store food waste before mixing into the digesters. “That’s all we thought we would ever do,” Darby says, “But when I started speaking to Chambers of Commerce and Kiwanis Clubs around Western Pennsylvania and Eastern Ohio, companies approached me and said they had material in packages and boxes. Could we do anything with that?”

His first reaction was that handling such material would be too much trouble, but he kept hearing about companies that needed to dispose of boxed food. Eventually the authority purchased a hammermill called a Turbo Separator (Scott Equipment Company) that could process not only boxed food but canned goods and products in plastic bottles or crates.

“We had all kinds of stuff coming in at that point,” Darby says. “We could just toss it into the Turbo Separator, which did a fantastic job of breaking it down and spitting out the packaging into a roll-off.”

Some packaging still presented problems. Items such as mayonnaise jars have hard lids that are more brittle than the rest of the container. “Those lids began to shatter,” he says. “Small flakes started getting into our process, and we don’t want that in our biosolids.”

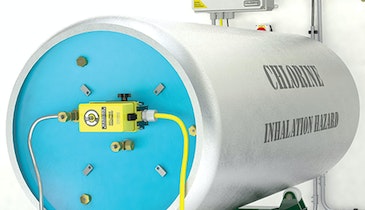

That prompted Hermitage to add a third piece of equipment, an eCrusor de-packaging system (Veolia). It uses a pair of augers to squeeze the food out of the packaging and doesn’t shatter the lids. “Today we have all three systems in place,” Darby says. “Depending on the product, we can run any one of them or all three.”

Certificates of destruction

Hermitage never had to be aggressive marketing its food waste recycling service; food waste brokers contacted the utility about handling various products. One asked if Hermitage could handle 300 tons of ice cream after a sample tested positive for Listeria.

“We gave them a price to take it, and we created a certificate of destruction that the FDA then approved,” Darby says. “Now for every load we issue a certificate showing that it was destroyed in an environmentally sound process.”

Some of the packaging goes into landfills, but some is recyclable and generates revenue. Aluminum beverage cans are drained in the perforator and packaged into 400- to 500-pound bales that are sold. Wooden pallets are sold to local buyers. Pallets marked with company logos are saved, and the owners pay Hermitage for storing them until they are retrieved.

“We’ve become a little bit of a recycling center as well as a wastewater operation and a renewable energy facility,” Darby says.

The authority doesn’t handle restaurant or post-consumer waste. “Everything we get is pre-consumer,” says Darby. “It has never been on anyone’s table. It’s all material that has been sitting in a warehouse somewhere too long and it’s about to expire, or it already has expired.

“There may be nothing wrong with it whatsoever, but because it has that expiration date on it, they can’t sell it. But we can get a benefit out of it, create energy and substantially reduce the impact on landfills.”

Lessons learned

Food waste processing has been beneficial to the authority and the food companies. It helps the authority produce more electricity and generate revenue, while enabling food distributors to handle waste products for a lower cost than landfilling.

One thing Darby would do differently is to build more redundancy into the system. The hydrolysis tank where the food wastes are stored isn’t large enough, and if it is full additional material has to be rejected. He’d also like more biogas storage so the plant would never have to flare — that could happen if one generator is down for maintenance and the storage ball is full.

One unanticipated problem was the acidity of the biosolids in the thermophilic digester. The pH between 4 and 5 is much lower than in the other digesters. As a result, some of the original ductile iron piping corroded and had to be replaced with stainless steel. Some pumps also had to be replaced.

“The whole process has been a very interesting learning experience for all of us,” Darby says. ”At the time we started this, my wastewater plant team members weren’t quite sure if my head was screwed on right. But we all adapted and we’ve found that receiving food waste is a very good revenue stream for our community.

“As an example, we haven’t had a sewer rate increase for 10 years. That’s because we’re getting paid to receive the organics and keep it out of the landfill.”